Three new papers published in Science, a multi-year research collaboration by the David Reich Institute, Max Planck and several other universities, have helped to bring the murky forces of prehistoric migration into much finer focus. The first focuses on the origins of the Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Indo-Anatolian languages through new genetic data, and the last focuses on the ethnic diversity of cities around the Roman empire and in early medieval Europe, which might be the subject of a future blog post or two. The second, and arguably the most revealing, is a study on the origins of the first farmers: the Pre-Pottery Anatolian Neolithic.

It's traditionally been assumed that Levantine hunter-cultivators, hailing from the Natufian culture, moved to Anatolia to build the first Neolithic societies. Gobekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe and other monumental sites have been seen as products of this transition, a 'last hurrah' of the hunters as lifestyles became more sedentary. However, this new study makes it clear that genetically, the makers of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (c.9000 - 7000 BCE), at communal centres like Catalhoyuk, were an ethnic fusion of hunter-gatherers from the west - the Pınarbaşı culture - and and those from the northern Fertile Crescent. The proto-farmers of the Levant, by contrast, contributed only a minimal amount to the farmer gene pool; where they did, it might have not been from a migration to Anatolia, but through intermixing with Pre-Pottery Anatolians in the Levant itself.

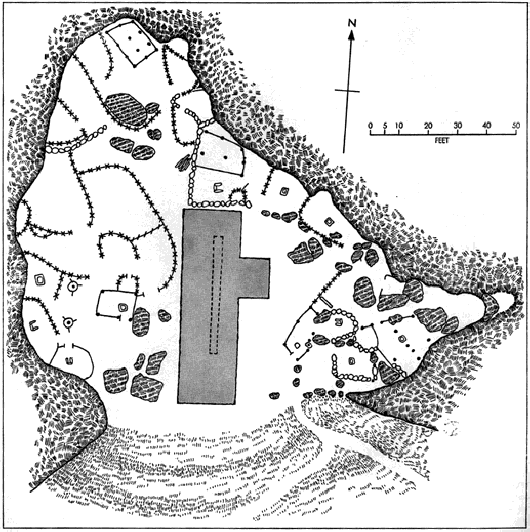

Proto-Neolithic cave settlement and cemetery at Shanidar, Iraq. Whether these farmers were aware of the much, much earlier Neanderthal burials much deeper in their cave is unknown.

This finding tallies, to an extent, with earlier modelling using the ASCEND software, which concluded that Pre-Pottery farmers in southeast Turkey were descended in part from people living in the Zagros Mountains, where several proto-Neolithic sites exist including Shanidar (~10,600 BP) and Chogha Golan (~12,000 BP). As hunter-gatherers for the majority of the time, these communities would have been highly mobile, and as a result northwest Mesopotamia and the Zagros must have been genetically and culturally close. It also underscores the fact that the 'Neolithic Revolution' was a steady, collaborative process, involving a lot of play, experimentation and reshaping of identities as climate conditions ebbed and flowed.

If we can establish how the first farming communities came together, the next step is understanding their motivations. There was no dramatic collapse in species availability or sudden biodiversity shift that would have made farming a necessity, although the local environment did become more arid following the Younger Dryas.

The genetic modelling shows that farming was not a eureka moment that swallowed everything else in its path wherever it went, but a lifestyle that hunter-gatherers in western Anatolia, Iran and possibly western Europe were aware of before any 'Revolution' took place. That there is evidence of domesticated wheat at Bouldnor Cliffs on the Isle of Wight - nearly 12000 years ago - surely indicates that plant cultivation was taking place on a far greater scale outside of the Neolithic homeland that previously thought.

References:

Lazaridis, I, Reich, D. et al (2022) Ancient DNA from Mesopotamia suggests distinct Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic migrations into Anatolia. Science, Vol 377, 6609 pp. 982-987 doi: 10.1126/science.abq0762

Comments

Post a Comment