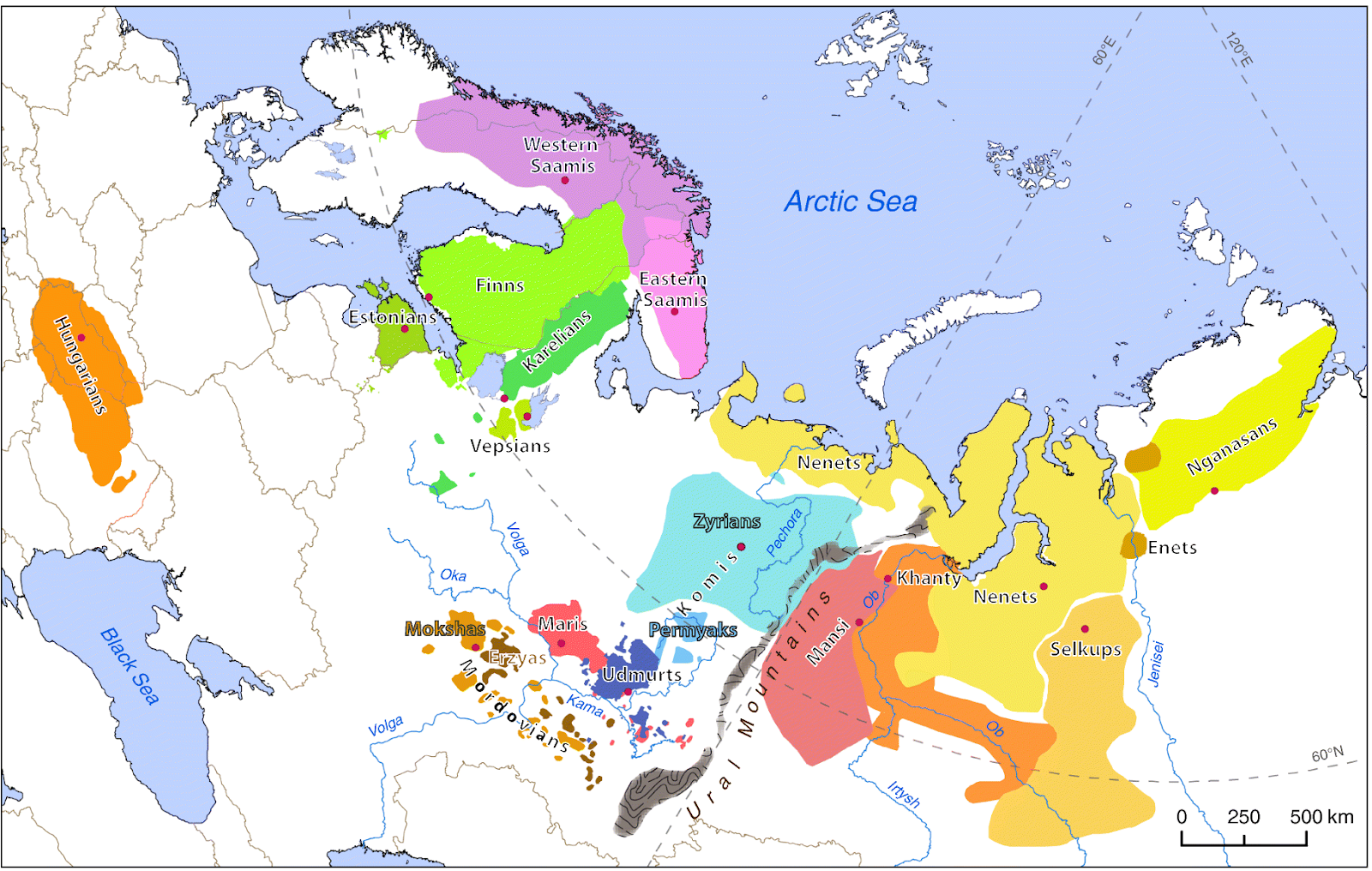

A new study, published on the 27th of April, makes some bold claims about the origin of the Uralic language family, which today includes the distantly related Finnish, Hungarian and Samoyedic. Today, it's divided into two groups east and west of the Ural mountains, but around 4,500 years ago it was one continues language spoken with various accents and dialects across western Siberia, which is hinted at by a word for the cedar tree common to all of the branches, which only grows north of the steppe.

The study claims that the 4.2 kiloyear event, a drastic period of drought in the Mediterrnaean and wetter climate in northern Eurasia, facilitates the spread of early Uralic speakers westwards to the Baltic Sea and eastern Europe, where they mingled with Proto-Indo-Iranian horse riders and settlers to produce what is archaeologically known as the 'Seima-Turbino Transcultural Phenomenon', defined by spearheads and axes. This phenomena was spread through rivers and smaller waterways, and the same basic dynamic of east-west trade continued well into the Middle Ages. As the centuries progressed, Uralic cultures and the Indo-Iranian cultures around the Caspian sea, notably the Sinshasta culture (2050–1750 BCE) developed a symbiotic relations where the Uralic people would collect and extract raw materials and trade them to Indo-Iranians at river confluences, allowing their families and animals to recover from the arid, overgrazed conditions of the steppe.

At this point, early Proto-Uralic apparently matures into Common Uralic, now incorporating Indo-Iranian and other loanwords such as the word for 'honeybee'. From a distant origin with the Volosovo culture of the Oka and Kama rivers about 6,000 BP, the flourishing Uralic languages spread to northern Europe and the Arctic Ocean early on, probably via reindeer herding and fur-trading. After about 500 BCE, the Samoyedic languages split and drifted towards the east.

Grünthal, R., Heyd, V., Holopainen, S., Janhunen, J. A., Khanina, O., Miestamo, M., ... & Sinnemäki, K. (2022). Drastic demographic events triggered the Uralic spread. Diachronica.

Comments

Post a Comment