The final centuries of the Bronze Age, with all its drama, mayhem and sabre-rattling, has been under increased archaeological interest in recent years, not least because of the decipherment of ancient texts from Ugarit and other sites in the Levant, which give us a great deal of information into the fragility of the palace societies of the day. New scientific techniques, primarily isotope analysis of human skeletons, also provides the potential to track the individual movements of warriors and their families, and by extension proving or disproving the 'Sea Peoples' narrative, which has been blamed from the early 20th century for the decline of the eastern Mediterranean , in the same way that barbarians were (and still are) blamed for the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

There is one piece of the Bronze Age puzzle, however, that continues to elude archaeologists. This is the 'black earth' or, in Italian, terramare cultural horizon, an archaeological culture across the Po valley in the Late Bronze Age, from roughly 1770 - 1150 BCE. Living in marshy alluvial environments, terramare communities constructed quadrangular or trapezoidal settlements of stilt-houses in a grid fashion, similar to what is seen in Roman settlements a millennium later. Unusually for Bronze Age societies outside of state capitals or major trading centres (such as Avaris, the Hyksos capital, which became the largest city in the world in the 17th century BCE), terramare settlements became larger, up to 20 hectares or more, and more densely packed overall. Similar stilt-house dwelling cultures surrounded them, such as the Polada culture of Lombardy and the lake-villages of the Alpine region, but the scale of the terramare suggests that they were either politically organised as independent city-states, imitating the other, or were one large tribal federation, perhaps like the 'loose league' of Etruscan cities in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE.

While this all seems out-of-the-ordinary enough, challenging the traditional picture of a wild, hairy and lawless Europe compared to a complex, ostentatious and decadent eastern Mediterranean passed down since the tales of Odysseus, it seems that the terramare people simply vanished into thin air, leaving their settlements perfectly intact, within the space of about ten to twenty years, around 1150 BCE. Based off settlement sizes, that implies an emigration, or rapid dispersal of nearly 200,000 people, a pretty dramatic change when considering the total population of Europe then was between 10 and 13 million. Put into more context, the migration of the Vandals, recorded with horror by contemporary Christian writers, into north Africa, was of around 40,000 people. So, what happened?

The archaeology indicates that changes were already underway before the total collapse, with larger settlements absorbing smaller, older settlements and consolidating more territory for themselves. Certainly, such a rapid and complete exodus could have only been possible with this kind of centralising authority; the only alternative would be a mass panic caused by a natural disaster or major battle, for which there is no evidence. An interesting theory put forward by the Italian archaeologist Andrea Cardarelli is that worsening environmental conditions, exacerbated by failed agricultural policies, recurring droughts and the demands of a growing population, reached such a degree that a collective decision was made to abandon ship.

Even more tantalisingly, he suggests a connection between the migration of the terramare and the Pelasgian migration recounted, a millenia later, by the Greek author Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who claims that the Pelasgians, one of the original tribes of the pre-Greek mainland (along with the Leleges, Arcadians and others), migrated to the Po valley from the Peleponnese during a time of hardship. They apparently quickly prospered at the expense of the neighbours, but were soon affected by drought and water pollution. After leaving votive offerings to the gods, they departed and set sail to Greece once again. He also quotes another author, Myrsilus of Lesbos, who claims that some of these people stayed behind to be known as the Tyrrhenians, better known as the Etruscans, while others took to the northern Aegean islands (particularly Lemnos) and became known as the Pelasgians.

That last point is interesting, as the ancient Lemnian language, attested by the Lemnos Stele (c.510 BCE), is closely connected to Etruscan. Overall, however, the account of a brief settlement and re-migration contradicts the archaeology, which finds no change in basic material culture between the Middle and latest Bronze Age. A possibility is that terramare descendants, resettling in Greece, the Aegean, Cyprus and other places, preserved a folk memory of a migration from northern Italy, which was re-interpreted by Greek authors to support their idea that all Italic peoples descended from legendary Greek heroes.

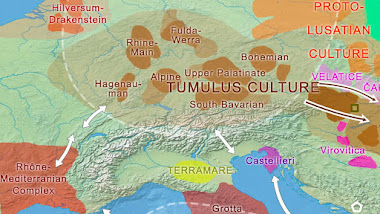

The core of the story, that worsening climate led to the wholesale abandonment of the region, appears to be true. Further along the Po, the Polada culture seems to have disapeared about the same time, completely replaced by the more central European-looking Canegrate culture. The sudden abandonment might have had something to do with pressure from Urnfield / Tumulus culture groups, such as the proto-Villanovans, who made their way into Italy shortly after the terramare disappeared. While no battlefield has been discovered, the threat of warfare in late Bronze Age Europe was real enough; at the same time in Tollense, northern Germany, more than 10,000 warriors on either side fought to the death for control of important trade routes.

If the migration can be explained, what about the migrants? Can they be found in the material record of Dark Age Greece or areas in the east? Unfortunately, as the terramare bore the same general axe types and spearheads as other Italian cultures, it is impossible to tell if migrant warriors ever found themselves serving Greek chieftains or eventually drifted back to their mother peninsula. On the other hand, they did have distinct swords known as Cetona or Naue-type swords, which have been found in Ugarit and other places in the eastern Mediterranian. These have usually been associated with the more warlike, dramatic Urnfielders, but given that 20% of the 200,000 migrants, at the most, would have been trained warriors, many could have easily wound up in the Levant. One Naue-type sword, found in Mycenae, has been provenanced using XRF to the Veneto region of northern Italy; exactly where the terramare people would have made their way through.

Recent speculation (such as by Dan Davis in his excellent video on the culture) links the terramare directly with the Sea Peoples, who from Egyptian reliefs and material culture we know to have been a smorgasbord of mercenaries and migrant families from all backgrounds, primarily from the Aegean and the western Mediterranean. Chronologically, however, if the abandonment is dated to 1150 BCE, this dates it after the Sea Peoples turn up as enemies of the pharaoh and after they begin to troube coastal states in the Levant. On the other hand, Dan and other online authors may have a point, if the Sea Peoples are not seen as a 'people' in any ethnic sense, but a social phenomenon that lasted for several centuries.

So to conclude, do we know why they dissapeared? For the most part, yes. Were they the Sea Peoples? Well, yes, no, maybe - a bit of both.

References:

Cardarelli, A. (2009). The collapse of the Terramare culture and growth of new economic and social systems during the Late Bronze Age in Italy. The Collapse of the Terramare Culture and growth of new economic and social systems during the Late Bronze Age in Italy, 449-520.

Jung, R., & Mehofer, M. (2008). A sword of Naue II type from Ugarit and the historical significance of Italian-type weaponry in the Eastern Mediterranean. Aegean Archaeology, 8, 111-136.

Comments

Post a Comment