The Anglo-Saxons have a reputation of being somewhat insular, at the mercy of far-travelling Vikings who plundered their coasts and set their settlements ablaze, and it is only with the conquest of England by Cnut in 1016 that they are though of as belonging to a 'north Atlantic' world connected with western Europe, Scandinavia, Greenland and the coasts of Spain.

The translation, and the addition of the travelogue of the Norse sailor Ohthere, to the 5th-century historical text of the Spaniard Paulus Orosius, the Historiae Adversus Paganos, however, does indicate that by the time of King Alfred, there was an awareness of lands as far as north-west Russia (referencing the area of Perm or Beormas) and the Ob river (the area around which might be called 'Fenland' by Ohthere's account).

Yet as far as knowledge of the Mediterranean, Africa and Asia goes, the consensus is that Anglo-Saxon England understood them only in Biblical terms, or from passing references in surviving Roman manuscripts. Several Anglo-Saxon kings undertook pilgrimages to Rome, and from an early period the Kingdom of Kent was dynastically wedded to the Kingdom of the Franks; but otherwise world beyond northwest Europe was a strange and fantastical place.

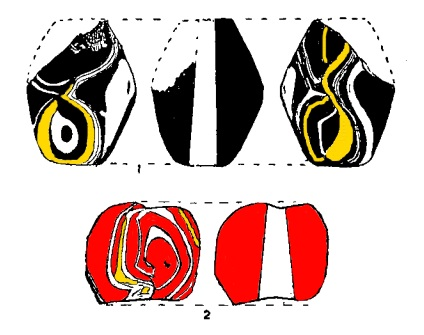

On the other hand, this can be challenged by a string of under-reported archaeological finds. Beads of a clearly Anglo-Saxon style were uncovered in the 1960s and the late 1970s, not only on the European mainland but in Sudan, and on the coast of Tanzania near the modern-day port city of Dar-es-Salaam. The same site in Tanzania is also the suspected location of the port of Rhapta, a classical emporium that is known, principally, from two sources: the navigational handbook, the Periplous of the Erythrian Sea by an unknown author, and the geographical treatise Geographica by Ptolemy, both dating to the 1st century CE.

We also know from scattered references and ecclesial accounts, such as the Christian Topography of Cosmas Indicopleustes - 'Cosmas who travelled to India' - that contacts between the Mediterranean and the Indian ocean continued well into the early Medieval period. Could this mean, therefore, that having heard of the wealth of Rhapta from Byzantine merchants, an Anglo-Saxon trader found his way to Rhapta and traded beads for ivory, coral, spice or slaves?

Anglo-Saxon (or Frankish) beads found near Dar-es-Salaam, drawn after Harding (1978) and colourized by C. Green (2016)

A more likely alternative, raised by Crawford (1951) in his initial report of the Sudanese finds, is that they were traded to a port in Egypt, probably Alexandria, and were gradually exchanged down-the-line, either through the Nile or along the Red Sea coasts, until they were purchased by an Ethiopian or south Arabian merchant with business connections to Rhapta. The beads discovered by the archaeological work are relatively common in Anglo-Saxon England and in north-western France, so it is hard to think that one sailor or trader would venture to the other side of the known world, or even beyond, to exchange a handful of beads in return for local goods. One piece of evidence in support of this is that the sixth-century monk Cosmas of the Christian Topography was himself from Alexandria, and must have collected information about the Christian communities around the Indian ocean through the trade and communication that flowed into the city.

It is also interesting to note that exchange with the African coast went the other way. Cowrie shells are known from Viking hoards such as the Cuerdale Hoard, which suggest indirect contact with the Indian ocean in some way - probably through the court of Baghdad, and from Romano-British sites. However, they have also known, sometimes together with amethysts, in early medieval contexts, concentrated along the North Sea coast and the area of the former Kingdom of Kent in particular. Both cowrie shells and amethsysts are found in great quantities across the Indian ocean coastline. Although this equally supports contact, if very indirect, with India and the Arabian Peninsula, many of these could have had their source on the East African coast. These two commodities complemented a long-standing trade in ivory and incense, probably from the horn of Africa.

Could an Anglo-Saxon trader have visited the coast of Tanzania? The beads may well have been personal items, exchanged as a gesture of goodwill - or, more darkly, as a token of captivity after ending up imprisoned or enslaved by an Arabian pirate captain or an East African chieftain. Perhaps their owner was not a trader, but a priest or missionary; evangelical missions to southern India occurred during the late Roman period and continued, at the behest of Alfred the Great, into the ninth century CE. Missions had already successfully converted the kingdom of Ethiopia a few centuries prior, and Christianity gradually permeated the upper reaches of the Nile, converting the rulers of the kingdoms of Nobatia and Alodia by at least the seventh century.

The Islamic world, at least, was actively engaged in attempting to convert the East African populace, as the construction of a coral-stone mosque at the nearby port of Shanga, at the same period, attests to. While it may not have been an organized effort, some attempt could well have been made to convert this faraway coast.

If there was contact, however distant. how long did it last? The date range of the cowrie shells, amethysts and the glass beads found at Rhapta suggest a period between the seventh and early tenth centuries, roughly corresponding to the 'mature' Anglo-Saxon period and an intensification of connections between the British Isles and the wider world.

The ivory trade, although largely supported by walrus ivory from Greenland and Scandinavia, never ceased, on the other hand. Anglo-Saxons were clearly aware of the wealth of the East immediately after the Norman conquest, as several parties of thegns and earls, led by a mysterious and otherwise unknown Siward Barn, fled to enlist as bodyguards of the Byzantine Emperor, and some went further still to establish colonies along the north-eastern Black Sea coast, known collectively as Nova Anglia. These runaway English are also recorded as fighting in the Crusades, bringing them close with the Islamic world.

To sum up, these scanty finds indicate that Anglo-Saxon England was dimly aware of East Africa and the trading world of the Indian Ocean, if mostly from antiquated late Roman manuscripts, and actively participated in commercial exchange. They may have even sent priests; as their missions to India, southern Norway, pagan northern Germany, and their later religious activity in the Crimea (lasting until the 15th century) demonstrate, they were not afraid of sticking their noses into heathen lands.

References:

Green, C. (2016) 'The Anglo-Saxons abroad? Some early Anglo-Saxon finds from France and East Africa'. Available at: https://www.caitlingreen.org/2016/05/anglo-saxon-finds-france-africa.html#fn8 [Accessed 4 April 2022]

J. R. Harding, 'Glass beads and early trading posts on the east coast of Africa', South African Archaeological Bulletin, 33 (1978)

O. G. S. Crawford et al, The Welcome Excavations in the Sudan, volume III: Abu Geili and Saqadi & Dar el Mek (London, 1951)

Comments

Post a Comment